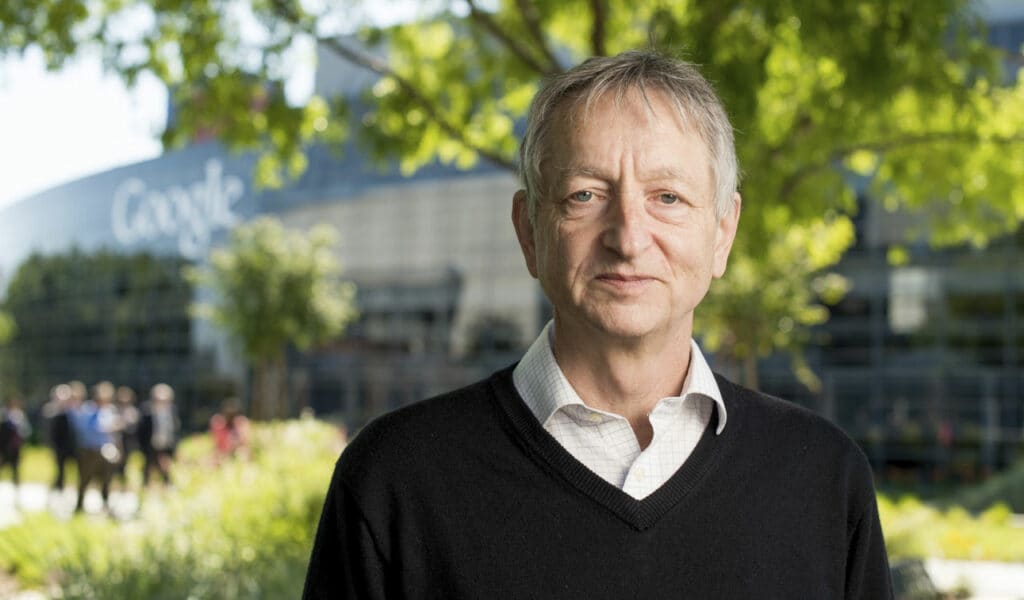

인공지능, AI의 대부로 널리 알려진 제프리 힌튼(Geoffrey Hinton, 75세) 박사가 구글을 떠나면서 인공지능 발전으로 인한 위험성이 증가하고 있다고 경고했습니다.

제프리 힌튼은 구글을 떠나면서 뉴욕타임스에 성명서를 보냈고 BBC와 인터뷰를 통해서 인공지능의 위험성을 경고하기도 했습니다.

여기에서는 제프리 힌튼이 구글을 떠나기 며칠전 MIT와의 인터뷰 내용을 번역, 소개해 봤습니다.

제프리 힌튼이 자신이 만든 기술을 두려워하는 이유에 대해 이야기합니다.

“갑자기 이런 것들이 우리보다 더 똑똑해질 것인지에 대한 나의 생각이 바뀌었습니다.” “I have suddenly switched my views on whether these things are going to be more intelligent than us.”

윌 더글러스 헤븐

2023년 5월 2일

구글을 그만둔다는 충격적인 발표가 있기 나흘 전, 런던 북쪽의 예쁜 거리에 있는 그의 집에서 제프리 힌튼을 만났습니다.

제프리 힌튼은 딥러닝의 선구자로서 현대 인공 지능의 핵심에 있는 가장 중요한 기술을 개발하는 데 기여했지만, 10년간의 구글 생활을 마치고 이제 AI에 대한 새로운 고민에 집중하기 위해 물러납니다.

GPT-4와 같은 새로운 대규모 언어 모델의 기능에 놀라움을 금치 못한 힌튼은 이제 자신이 도입한 기술에 수반될 수 있는 심각한 위험에 대한 대중의 인식을 높이고자 합니다.

대화를 시작할 때 제가 식탁에 앉자 힌튼이 걸음을 재촉하기 시작했습니다.

수년 동안 만성 허리 통증에 시달려온 힌튼은 거의 앉지 않습니다. 한 시간 동안 저는 그가 방의 한쪽 끝에서 다른 쪽 끝으로 걸어가는 모습을 지켜보면서 그가 말하는 동안 고개를 돌렸습니다. 그리고 그는 할 말이 많았습니다.

제프리 힌튼이 구글을 떠나는 이유

딥러닝 연구로 2018년 튜링상을 얀 르쿤, 요슈아 벤지오와 함께 공동 수상한 75세의 컴퓨터 과학자인 그는 이제 다른 분야로 전환할 준비가 되었다고 말합니다.

“많은 세부 사항을 기억해야 하는 기술적인 작업을 하기에는 너무 나이가 들었습니다.”

“아직은 괜찮지만 예전만큼은 아니어서 짜증이 나죠.”

하지만 이것이 그가 구글을 떠나는 유일한 이유는 아닙니다. 힌튼은 “좀 더 철학적인 일”에 시간을 투자하고 싶다고 말합니다. 그리고 그 작업은 AI가 재앙이 될 수 있다는 작지만 그에게 매우 현실적인 위험에 초점을 맞출 것입니다.

구글을 떠나면 구글 임원으로서 겪어야 하는 자기 검열 없이 자신의 생각을 말할 수 있게 될 것입니다.

“저는 AI가 Google 비즈니스와 어떻게 상호 작용할지 걱정할 필요 없이 AI 안전 문제에 대해 이야기하고 싶습니다.”

“구글에서 월급을 받는 한 그렇게 할 수 없습니다.”

그렇다고 해서 힌튼이 구글에 불만이 있는 것은 아닙니다. “놀랄 수도 있습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “제가 구글에 대해 말하고 싶은 좋은 점이 많은데, 제가 더 이상 구글에 있지 않으니 훨씬 더 믿을 만합니다.”

힌튼은 차세대 대규모 언어 모델, 특히 OpenAI가 3월에 출시한 GPT-4를 통해 기계가 자신이 생각했던 것보다 훨씬 더 똑똑해질 수 있다는 사실을 깨달았다고 말합니다. 그리고 그는 그 결과가 어떻게 나타날지 두렵습니다.

“기계는 우리와 완전히 다른 존재입니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “마치 외계인이 착륙했는데 사람들이 영어를 너무 잘해서 깨닫지 못하는 것 같다는 생각이 들 때가 있습니다.”

기초, Foundations

힌튼은 1980년대에 동료들과 함께 제안한 ‘역전파’라는 기법에 대한 연구로 가장 잘 알려져 있습니다.

간단히 말해 기계가 학습할 수 있도록 하는 알고리즘입니다. 이 기술은 컴퓨터 비전 시스템부터 대규모 언어 모델에 이르기까지 오늘날 거의 모든 신경망을 뒷받침합니다.

2010년대 들어서야 비로소 역전파를 통해 훈련된 신경망의 성능이 본격적으로 빛을 발하기 시작했습니다.

두 명의 대학원생과 함께 작업한 힌튼은 컴퓨터가 이미지에서 물체를 식별하는 데 있어 자신의 기술이 다른 어떤 기술보다 우수하다는 것을 보여주었습니다. 또한 오늘날의 대규모 언어 모델의 선구자인 신경망을 훈련시켜 문장의 다음 문자를 예측하도록 했습니다.

이 대학원생 중 한 명인 일리야 수츠케버는 OpenAI를 공동 설립하고 ChatGPT의 개발을 이끌었습니다.

힌튼은 “우리는 이 기술이 놀라울 수 있다는 것을 처음 알았습니다.”라고 말합니다. “하지만 좋은 결과를 얻으려면 엄청난 규모로 이루어져야 한다는 사실을 깨닫는 데 오랜 시간이 걸렸습니다.”

1980년대만 해도 신경망은 농담에 불과했습니다. 당시에는 심볼릭 AI로 알려진, 지능은 단어나 숫자와 같은 기호를 처리하는 것과 관련이 있다는 생각이 지배적이었습니다.

하지만 힌튼은 확신하지 못했습니다. 그는 뉴런과 뉴런 사이의 연결이 코드로 표현되는 두뇌의 소프트웨어 추상화인 신경망에 대해 연구했습니다. 뉴런이 연결되는 방식, 즉 뉴런을 표현하는 데 사용되는 숫자를 변경함으로써 신경망을 즉석에서 다시 연결할 수 있습니다. 즉, 학습할 수 있도록 만들 수 있습니다.

힌튼은 “아버지가 생물학자였기 때문에 생물학적 관점에서 사고했습니다.”라고 말합니다. “그리고 상징적 추론은 생물학적 지능의 핵심이 아닙니다.

“까마귀는 퍼즐을 풀 수 있지만 언어가 없습니다. 까마귀는 기호 문자열을 저장하고 조작하는 방식으로 퍼즐을 푸는 것이 아닙니다. 까마귀는 뇌의 뉴런 간 연결 강도를 변화시킴으로써 퍼즐을 풀 수 있습니다. 따라서 인공 신경망에서 연결의 강도를 변경하여 복잡한 것을 학습할 수 있어야 합니다.”

새로운 지능, A new intelligence

힌튼은 40년 동안 인공 신경망을 생물학적 신경망을 모방한 부실한 시도로 여겨왔습니다. 하지만 이제는 상황이 달라졌다고 생각합니다. 생물학적 두뇌가 하는 일을 모방하려고 노력하면서 더 나은 것을 생각해냈다고 그는 생각합니다. “그런 걸 보면 무섭습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “갑자기 뒤집어지는 거죠.”

힌튼의 두려움은 많은 사람들에게 공상 과학 소설의 소재처럼 느껴질 것입니다. 하지만 그의 사례는 이렇습니다.

이름에서 알 수 있듯이 대규모 언어 모델은 방대한 수의 연결이 있는 대규모 신경망으로 만들어집니다. 하지만 뇌에 비하면 아주 작습니다.

힌튼은 “우리의 뇌는 100조 개의 연결로 이루어져 있습니다.”라고 말합니다. “대규모 언어 모델은 최대 5조 개에서 최대 1조 개까지 연결됩니다.

하지만 GPT-4는 한 사람이 알고 있는 것보다 수백 배 더 많은 것을 알고 있습니다. 따라서 실제로는 우리보다 훨씬 더 나은 학습 알고리즘을 가지고 있을 수도 있습니다.”

두뇌에 비해 신경망은 학습에 취약한 것으로 널리 알려져 있는데, 신경망을 훈련하는 데 방대한 양의 데이터와 에너지가 필요하기 때문입니다. 반면에 두뇌는 신경망에 비해 훨씬 적은 에너지를 사용하여 새로운 아이디어와 기술을 빠르게 습득합니다.

“사람들은 일종의 마법을 가진 것 같았습니다.”라고 힌튼은 말합니다. “대규모 언어 모델 중 하나를 가져다가 새로운 작업을 수행하도록 훈련시키면 그 주장의 근거가 사라집니다. 새로운 작업을 매우 빠르게 학습할 수 있습니다.”

힌튼은 대규모 언어 모델과 같이 사전 훈련된 신경망이 몇 가지 예제만 주어져도 새로운 작업을 수행하도록 훈련할 수 있는 ‘단발성 학습’에 대해 이야기하고 있습니다. 예를 들어, 그는 이러한 언어 모델 중 일부는 직접 학습한 적이 없음에도 불구하고 일련의 논리적 진술을 하나의 인수로 묶을 수 있다고 말합니다.

사전 학습된 대규모 언어 모델과 인간의 학습 속도를 비교하면 인간의 우위가 사라진다고 그는 말합니다.

대규모 언어 모델이 많은 것을 만들어낸다는 사실은 어떨까요? AI 연구자들이 ‘환각’이라고 부르는 이러한 오류(힌튼은 심리학에서는 ‘혼동’이라는 용어를 더 선호하지만)는 종종 기술의 치명적인 결함으로 간주됩니다.

이러한 오류를 생성하는 경향은 챗봇을 신뢰할 수 없게 만들며, 많은 사람들은 이러한 모델이 말하는 내용을 제대로 이해하지 못한다는 것을 보여줍니다.

이에 대해서도 힌튼은 헛소리는 버그가 아니라 기능이라는 대답을 내놓았습니다. “사람들은 항상 거짓말을 합니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. 반쪽짜리 진실과 잘못 기억된 세부 사항은 인간 대화의 특징입니다: “컨패뷸레이션은 인간 기억의 특징입니다. 이 모델도 사람과 똑같이 무언가를 하고 있습니다.”

힌튼은 인간은 대개 어느 정도 정확하게 컨파뷸레이션을 한다는 점이 다르다고 말합니다. 힌튼에게 있어, 무언가를 만들어내는 것은 문제가 되지 않습니다. 컴퓨터는 조금 더 연습이 필요할 뿐입니다.

또한 우리는 컴퓨터가 옳고 그름을 판단하는 것이 아니라 그 중간에 있는 것을 기대합니다. “우리는 컴퓨터가 사람처럼 허풍을 떨기를 기대하지 않습니다.”라고 힌튼은 말합니다. “컴퓨터가 그렇게 하면 우리는 컴퓨터가 실수했다고 생각합니다. 하지만 사람이 그렇게 하면 그게 바로 사람이 일하는 방식입니다. 문제는 대부분의 사람들이 사람들이 일하는 방식에 대해 절망적으로 잘못된 견해를 가지고 있다는 것입니다.”

물론 뇌는 자동차 운전, 걷는 법 배우기, 미래 상상하기 등 여전히 컴퓨터보다 더 많은 일을 더 잘합니다. 그리고 뇌는 커피 한 잔과 토스트 한 조각을 먹으면서도 이 모든 일을 해냅니다. “생물학적 지능이 진화할 당시에는 원자력 발전소도 없었습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다.

하지만 힌튼의 요점은 우리가 높은 컴퓨팅 비용을 기꺼이 지불한다면 신경망이 학습에서 생물학을 이길 수 있는 결정적인 방법이 있다는 것입니다. (그리고 이러한 비용이 에너지와 탄소 측면에서 무엇을 수반하는지 잠시 생각해 볼 필요가 있습니다.)

학습은 힌튼의 주장의 첫 번째 줄에 불과합니다.

두 번째는 소통입니다. “여러분이나 제가 무언가를 배우고 그 지식을 다른 사람에게 전수하고 싶을 때, 단순히 복사본만 보낼 수는 없습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “하지만 저는 각자의 경험을 가진 10,000개의 신경망을 가질 수 있고, 그 중 누구라도 자신이 배운 것을 즉시 공유할 수 있습니다. 이는 엄청난 차이입니다. 마치 만 명의 사람이 있는데 한 사람이 무언가를 배우면 우리 모두가 그것을 아는 것과 같습니다.”

이 모든 것이 합쳐져 무엇을 의미할까요?

힌튼은 이제 세상에는 동물의 뇌와 신경망이라는 두 가지 유형의 지능이 있다고 생각합니다. “완전히 다른 형태의 지능입니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “새롭고 더 나은 형태의 지능입니다.”

엄청난 주장입니다. 하지만 AI는 양극화된 분야이기 때문에 그의 말에 비웃는 사람과 동의하며 고개를 끄덕이는 사람을 쉽게 찾을 수 있습니다.

또한 이 새로운 형태의 지능이 존재한다면 그 결과가 유익할지 아니면 종말이 될지에 대해서도 의견이 분분합니다.

“초지능이 좋을지 나쁠지는 낙관주의자인지 비관주의자인지에 따라 크게 달라집니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “가족 중 누군가가 중병에 걸리거나 차에 치일 확률과 같이 나쁜 일이 일어날 위험을 추정해 보라고 하면 낙관주의자는 5%라고 하고 비관주의자는 그런 일이 일어날 확률이 보장된다고 할 것입니다. 하지만 경미한 우울증을 앓고 있는 사람은 그 확률이 40% 정도라고 말할 것이고, 대개는 그 말이 맞을 것입니다.”

힌튼은 어느 쪽인가요? “저는 경미한 우울증입니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “그래서 무서워요.”

모든 것이 잘못될 수 있는 방법, How it could all go wrong

힌튼은 이러한 도구가 새로운 기술에 대비하지 않은 인간을 조작하거나 죽이는 방법을 알아낼 수 있다는 점을 우려합니다.

“저는 갑자기 이런 것들이 우리보다 더 똑똑해질 것이라는 생각이 바뀌었습니다. 지금은 매우 근접해 있고 미래에는 우리보다 훨씬 더 똑똑해질 것이라고 생각합니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “우리는 어떻게 살아남을 수 있을까요?”

그는 특히 사람들이 자신이 생명을 불어넣는 데 도움을 준 도구를 활용하여 선거와 전쟁과 같은 가장 중대한 인간 경험의 저울추를 기울일 수 있다는 점을 우려합니다.

“이 모든 것이 잘못될 수 있는 한 가지 방법이 있습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. “우리는 이러한 도구를 사용하려는 사람들 중 상당수가 푸틴이나 드산티스 같은 악당이라는 것을 알고 있습니다. 그들은 전쟁에서 승리하거나 유권자를 조작하는 데 이 도구를 사용하려고 합니다.”

힌튼은 스마트 머신의 다음 단계는 작업을 수행하는 데 필요한 중간 단계인 자체 하위 목표를 생성하는 기능이라고 생각합니다. 이러한 능력이 본질적으로 부도덕한 일에 적용되면 어떤 일이 벌어질까요?

“푸틴이 우크라이나 사람들을 죽일 목적으로 초지능 로봇을 만들지 않을 거라고는 한순간도 생각하지 마세요.”라고 그는 말합니다. “그는 주저하지 않을 것입니다. 그리고 로봇이 잘 하길 원한다면 로봇을 세세하게 관리할 것이 아니라 로봇이 어떻게 해야 하는지 알아내길 원할 것입니다.”

이미 BabyAGI, AutoGPT와 같이 챗봇을 웹 브라우저나 워드 프로세서와 같은 다른 프로그램과 연결하여 간단한 작업을 함께 수행할 수 있도록 하는 실험적인 프로젝트가 몇 개 있습니다. 물론 작은 단계이긴 하지만 일부 사람들이 이 기술을 발전시키고자 하는 방향을 보여줍니다. 힌튼은 악의적 행위자가 기계를 장악하지 않더라도 하위 목표에 대한 다른 우려도 있다고 말합니다.

“생물학에서 거의 항상 도움이 되는 하위 목표가 있는데, 바로 더 많은 에너지를 얻는 것입니다. 따라서 가장 먼저 일어날 수 있는 일은 로봇이 ‘더 많은 전력을 얻자’고 말하는 것입니다. 모든 전기를 내 칩으로 다시 보내자’라고 말할 것입니다. 또 다른 훌륭한 하위 목표는 자신의 복사본을 더 많이 만드는 것입니다. 좋은 생각인가요?”

아닐 수도 있습니다. 하지만 메타의 수석 AI 과학자인 얀 르쿤은 이 전제에는 동의하지만 힌튼의 두려움에는 동의하지 않습니다. 르쿤은 “앞으로 기계가 인간보다 더 똑똑해질 것이라는 데는 의심의 여지가 없습니다.”라고 말합니다. “언제, 어떻게 되느냐의 문제이지 ‘만약’의 문제가 아닙니다.”

하지만 르쿤은 그 이후의 미래에 대해 완전히 다른 견해를 가지고 있습니다. “저는 지능형 기계가 인류에게 새로운 르네상스, 즉 새로운 깨달음의 시대를 열어줄 것이라고 믿습니다.”라고 르쿤은 말합니다. “저는 기계가 인간을 파괴하는 것은 말할 것도 없고 단순히 더 똑똑하다는 이유로 인간을 지배할 것이라는 생각에 전적으로 동의하지 않습니다.”

르쿤은 “인간 종 내에서도 가장 똑똑한 사람이 가장 지배적인 사람은 아닙니다.”라고 말합니다. “그리고 가장 지배적인 사람이 가장 똑똑한 사람도 아닙니다. 우리는 정치와 비즈니스에서 수많은 사례를 볼 수 있습니다.”

몬트리올 대학교 교수이자 몬트리올 학습 알고리즘 연구소의 과학 책임자인 요슈아 벤지오의 생각은 좀 더 불가지론적입니다. 그는 “이러한 두려움을 폄하하는 사람들의 말을 듣기는 하지만, 제프가 생각하는 정도의 위험은 없다고 확신할 만한 확실한 논거를 보지 못했습니다.”라고 말합니다. 하지만 두려움은 우리를 행동으로 옮기게 할 때만 유용하다고 그는 말합니다. “과도한 두려움은 우리를 마비시킬 수 있으므로 합리적인 수준에서 토론을 유지하도록 노력해야 합니다.”

그냥 찾아보기, Just Look up

힌튼의 최우선 과제 중 하나는 기술 업계의 리더들과 협력하여 그들이 함께 모여 위험이 무엇인지, 그리고 이에 대해 무엇을 해야 하는지 합의할 수 있는지 확인하는 것입니다.

그는 화학무기에 대한 국제적 금지가 위험한 AI의 개발과 사용을 억제하는 방법의 한 모델이 될 수 있다고 생각합니다. “완벽한 것은 아니지만 전체적으로 사람들은 화학무기를 사용하지 않습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다.

벤지오도 이러한 문제를 가능한 한 빨리 사회적인 차원에서 해결해야 한다는 힌튼의 의견에 동의합니다.

하지만 그는 AI의 발전이 사회가 따라잡을 수 있는 속도보다 더 빠르게 가속화되고 있다고 말합니다. 이 기술의 역량은 몇 달에 한 번씩 비약적으로 발전하지만 법률, 규제, 국제 조약은 몇 년이 걸립니다.

따라서 벤지오는 현재 우리 사회가 국가 및 글로벌 차원에서 조직되어 있는 방식이 이러한 도전에 대응할 수 있는지에 대해 의문을 품게 됩니다. “저는 우리가 지구의 사회 조직을 위한 상당히 다른 모델의 가능성에 대해 열려 있어야 한다고 생각합니다.”라고 그는 말합니다.

힌튼은 자신의 우려를 공유할 만한 권력자들을 충분히 확보할 수 있다고 생각할까요? 그는 모르죠. 몇 주 전, 그는 소행성이 지구를 향해 다가오는데 아무도 이에 대해 어떻게 해야 할지 합의하지 못하고 모두가 죽는다는 내용의 영화 를 봤는데, 이는 세계가 기후 변화에 대처하는 데 실패하고 있다는 우화입니다.

“AI도 마찬가지라고 생각합니다.”라고 그는 말합니다. 다른 큰 난치성 문제들도 마찬가지입니다. “미국은 10대 소년들의 손에서 공격용 소총(assault rifles)을 빼앗는 것에 동의하지도 않습니다.”라고 그는 말합니다.

힌튼의 주장은 냉정합니다. 심각한 위협에 직면했을 때 사람들이 집단적으로 행동하지 못하는 것에 대한 그의 암울한 평가에 저도 동의합니다.

AI가 고용 시장을 뒤흔들고, 불평등을 고착화하며, 성차별과 인종차별을 악화시키는 등 실질적인 해악을 끼칠 위험이 있다는 것도 사실입니다. 우리는 이러한 문제에 집중해야 합니다. 하지만 저는 여전히 대규모 언어 모델에서 로봇 군주로 도약할 수 없습니다. 제가 낙관주의자인지도 모르겠네요.

힌튼이 저를 배웅했을 때 봄날은 회색빛으로 변해 있었습니다. “얼마 남지 않았으니 즐기세요.” 그가 말했다. 그는 웃으며 문을 닫았습니다.

5월 3일 수요일 1시 30분(동부시간 기준)에 엠텍 디지털에서 열리는 윌 더글라스 헤븐과 힌튼의 라이브 인터뷰를 꼭 시청하세요. 티켓은 이벤트 웹사이트에서 구매할 수 있습니다.

제프리힌튼 인터뷰 원문

Geoffrey Hinton tells us why he’s now scared of the tech he helped build

“I have suddenly switched my views on whether these things are going to be more intelligent than us.”

Will Douglas Heaven

May 2, 2023

I met Geoffrey Hinton at his house on a pretty street in north London just four days before the bombshell announcement that he is quitting Google. Hinton is a pioneer of deep learning who helped develop some of the most important techniques at the heart of modern artificial intelligence, but after a decade at Google, he is stepping down to focus on new concerns he now has about AI.

Stunned by the capabilities of new large language models like GPT-4, Hinton wants to raise public awareness of the serious risks that he now believes may accompany the technology he ushered in.

At the start of our conversation, I took a seat at the kitchen table, and Hinton started pacing. Plagued for years by chronic back pain, Hinton almost never sits down. For the next hour I watched him walk from one end of the room to the other, my head swiveling as he spoke. And he had plenty to say.

The 75-year-old computer scientist, who was a joint recipient with Yann LeCun and Yoshua Bengio of the 2018 Turing Award for his work on deep learning, says he is ready to shift gears. “I’m getting too old to do technical work that requires remembering lots of details,” he told me. “I’m still okay, but I’m not nearly as good as I was, and that’s annoying.”

But that’s not the only reason he’s leaving Google. Hinton wants to spend his time on what he describes as “more philosophical work.” And that will focus on the small but—to him—very real danger that AI will turn out to be a disaster.

Leaving Google will let him speak his mind, without the self-censorship a Google executive must engage in. “I want to talk about AI safety issues without having to worry about how it interacts with Google’s business,” he says. “As long as I’m paid by Google, I can’t do that.”

That doesn’t mean Hinton is unhappy with Google by any means. “It may surprise you,” he says. “There’s a lot of good things about Google that I want to say, and they’re much more credible if I’m not at Google anymore.”

Hinton says that the new generation of large language models—especially GPT-4, which OpenAI released in March—has made him realize that machines are on track to be a lot smarter than he thought they’d be. And he’s scared about how that might play out.

“These things are totally different from us,” he says. “Sometimes I think it’s as if aliens had landed and people haven’t realized because they speak very good English.”

Foundations

Hinton is best known for his work on a technique called backpropagation, which he proposed (with a pair of colleagues) in the 1980s. In a nutshell, this is the algorithm that allows machines to learn. It underpins almost all neural networks today, from computer vision systems to large language models.

It took until the 2010s for the power of neural networks trained via backpropagation to truly make an impact. Working with a couple of graduate students, Hinton showed that his technique was better than any others at getting a computer to identify objects in images. They also trained a neural network to predict the next letters in a sentence, a precursor to today’s large language models.

One of these graduate students was Ilya Sutskever, who went on to cofound OpenAI and lead the development of ChatGPT. “We got the first inklings that this stuff could be amazing,” says Hinton. “But it’s taken a long time to sink in that it needs to be done at a huge scale to be good.” Back in the 1980s, neural networks were a joke. The dominant idea at the time, known as symbolic AI, was that intelligence involved processing symbols, such as words or numbers.

But Hinton wasn’t convinced. He worked on neural networks, software abstractions of brains in which neurons and the connections between them are represented by code. By changing how those neurons are connected—changing the numbers used to represent them—the neural network can be rewired on the fly. In other words, it can be made to learn.

“My father was a biologist, so I was thinking in biological terms,” says Hinton. “And symbolic reasoning is clearly not at the core of biological intelligence.

“Crows can solve puzzles, and they don’t have language. They’re not doing it by storing strings of symbols and manipulating them. They’re doing it by changing the strengths of connections between neurons in their brain. And so it has to be possible to learn complicated things by changing the strengths of connections in an artificial neural network.”

A new intelligence

For 40 years, Hinton has seen artificial neural networks as a poor attempt to mimic biological ones. Now he thinks that’s changed: in trying to mimic what biological brains do, he thinks, we’ve come up with something better. “It’s scary when you see that,” he says. “It’s a sudden flip.”

Hinton’s fears will strike many as the stuff of science fiction. But here’s his case.

As their name suggests, large language models are made from massive neural networks with vast numbers of connections. But they are tiny compared with the brain. “Our brains have 100 trillion connections,” says Hinton. “Large language models have up to half a trillion, a trillion at most. Yet GPT-4 knows hundreds of times more than any one person does. So maybe it’s actually got a much better learning algorithm than us.”

Compared with brains, neural networks are widely believed to be bad at learning: it takes vast amounts of data and energy to train them. Brains, on the other hand, pick up new ideas and skills quickly, using a fraction as much energy as neural networks do.

“People seemed to have some kind of magic,” says Hinton. “Well, the bottom falls out of that argument as soon as you take one of these large language models and train it to do something new. It can learn new tasks extremely quickly.”

Hinton is talking about “few-shot learning,” in which pretrained neural networks, such as large language models, can be trained to do something new given just a few examples. For example, he notes that some of these language models can string a series of logical statements together into an argument even though they were never trained to do so directly.

Compare a pretrained large language model with a human in the speed of learning a task like that and the human’s edge vanishes, he says.

What about the fact that large language models make so much stuff up? Known as “hallucinations” by AI researchers (though Hinton prefers the term “confabulations,” because it’s the correct term in psychology), these errors are often seen as a fatal flaw in the technology. The tendency to generate them makes chatbots untrustworthy and, many argue, shows that these models have no true understanding of what they say.

Hinton has an answer for that too: bullshitting is a feature, not a bug. “People always confabulate,” he says. Half-truths and misremembered details are hallmarks of human conversation: “Confabulation is a signature of human memory. These models are doing something just like people.”

The difference is that humans usually confabulate more or less correctly, says Hinton. To Hinton, making stuff up isn’t the problem. Computers just need a bit more practice.

We also expect computers to be either right or wrong—not something in between. “We don’t expect them to blather the way people do,” says Hinton. “When a computer does that, we think it made a mistake. But when a person does that, that’s just the way people work. The problem is most people have a hopelessly wrong view of how people work.”

Of course, brains still do many things better than computers: drive a car, learn to walk, imagine the future. And brains do it on a cup of coffee and a slice of toast. “When biological intelligence was evolving, it didn’t have access to a nuclear power station,” he says.

But Hinton’s point is that if we are willing to pay the higher costs of computing, there are crucial ways in which neural networks might beat biology at learning. (And it’s worth pausing to consider what those costs entail in terms of energy and carbon.)

Learning is just the first string of Hinton’s argument. The second is communicating. “If you or I learn something and want to transfer that knowledge to someone else, we can’t just send them a copy,” he says. “But I can have 10,000 neural networks, each having their own experiences, and any of them can share what they learn instantly. That’s a huge difference. It’s as if there were 10,000 of us, and as soon as one person learns something, all of us know it.”

What does all this add up to? Hinton now thinks there are two types of intelligence in the world: animal brains and neural networks. “It’s a completely different form of intelligence,” he says. “A new and better form of intelligence.”

That’s a huge claim. But AI is a polarized field: it would be easy to find people who would laugh in his face—and others who would nod in agreement.

People are also divided on whether the consequences of this new form of intelligence, if it exists, would be beneficial or apocalyptic. “Whether you think superintelligence is going to be good or bad depends very much on whether you’re an optimist or a pessimist,” he says. “If you ask people to estimate the risks of bad things happening, like what’s the chance of someone in your family getting really sick or being hit by a car, an optimist might say 5% and a pessimist might say it’s guaranteed to happen. But the mildly depressed person will say the odds are maybe around 40%, and they’re usually right.”

Which is Hinton? “I’m mildly depressed,” he says. “Which is why I’m scared.”

How it could all go wrong

Hinton fears that these tools are capable of figuring out ways to manipulate or kill humans who aren’t prepared for the new technology.

“I have suddenly switched my views on whether these things are going to be more intelligent than us. I think they’re very close to it now and they will be much more intelligent than us in the future,” he says. “How do we survive that?”

He is especially worried that people could harness the tools he himself helped breathe life into to tilt the scales of some of the most consequential human experiences, especially elections and wars.

“Look, here’s one way it could all go wrong,” he says. “We know that a lot of the people who want to use these tools are bad actors like Putin or DeSantis. They want to use them for winning wars or manipulating electorates.”

Hinton believes that the next step for smart machines is the ability to create their own subgoals, interim steps required to carry out a task. What happens, he asks, when that ability is applied to something inherently immoral?

“Don’t think for a moment that Putin wouldn’t make hyper-intelligent robots with the goal of killing Ukrainians,” he says. “He wouldn’t hesitate. And if you want them to be good at it, you don’t want to micromanage them—you want them to figure out how to do it.”

There are already a handful of experimental projects, such as BabyAGI and AutoGPT, that hook chatbots up with other programs such as web browsers or word processors so that they can string together simple tasks. Tiny steps, for sure—but they signal the direction that some people want to take this tech. And even if a bad actor doesn’t seize the machines, there are other concerns about subgoals, Hinton says.

“Well, here’s a subgoal that almost always helps in biology: get more energy. So the first thing that could happen is these robots are going to say, ‘Let’s get more power. Let’s reroute all the electricity to my chips.’ Another great subgoal would be to make more copies of yourself. Does that sound good?”

Maybe not. But Yann LeCun, Meta’s chief AI scientist, agrees with the premise but does not share Hinton’s fears. “There is no question that machines will become smarter than humans—in all domains in which humans are smart—in the future,” says LeCun. “It’s a question of when and how, not a question of if.”

But he takes a totally different view on where things go from there. “I believe that intelligent machines will usher in a new renaissance for humanity, a new era of enlightenment,” says LeCun. “I completely disagree with the idea that machines will dominate humans simply because they are smarter, let alone destroy humans.”

“Even within the human species, the smartest among us are not the ones who are the most dominating,” says LeCun. “And the most dominating are definitely not the smartest. We have numerous examples of that in politics and business.”

Yoshua Bengio, who is a professor at the University of Montreal and scientific director of the Montreal Institute for Learning Algorithms, feels more agnostic. “I hear people who denigrate these fears, but I don’t see any solid argument that would convince me that there are no risks of the magnitude that Geoff thinks about,” he says. But fear is only useful if it kicks us into action, he says: “Excessive fear can be paralyzing, so we should try to keep the debates at a rational level.”

Just look up

One of Hinton’s priorities is to try to work with leaders in the technology industry to see if they can come together and agree on what the risks are and what to do about them. He thinks the international ban on chemical weapons might be one model of how to go about curbing the development and use of dangerous AI. “It wasn’t foolproof, but on the whole people don’t use chemical weapons,” he says.

Bengio agrees with Hinton that these issues need to be addressed at a societal level as soon as possible. But he says the development of AI is accelerating faster than societies can keep up. The capabilities of this tech leap forward every few months; legislation, regulation, and international treaties take years.

This makes Bengio wonder whether the way our societies are currently organized—at both national and global levels—is up to the challenge. “I believe that we should be open to the possibility of fairly different models for the social organization of our planet,” he says.

Does Hinton really think he can get enough people in power to share his concerns? He doesn’t know. A few weeks ago, he watched the movie Don’t Look Up, in which an asteroid zips toward Earth, nobody can agree what to do about it, and everyone dies—an allegory for how the world is failing to address climate change.

“I think it’s like that with AI,” he says, and with other big intractable problems as well. “The US can’t even agree to keep assault rifles out of the hands of teenage boys,” he says.

Hinton’s argument is sobering. I share his bleak assessment of people’s collective inability to act when faced with serious threats. It is also true that AI risks causing real harm—upending the job market, entrenching inequality, worsening sexism and racism, and more. We need to focus on those problems. But I still can’t make the jump from large language models to robot overlords. Perhaps I’m an optimist.

When Hinton saw me out, the spring day had turned gray and wet. “Enjoy yourself, because you may not have long left,” he said. He chuckled and shut the door.

Be sure to tune in to Will Douglas Heaven’s live interview with Hinton at EmTech Digital on Wednesday, May 3, at 1:30 Eastern time. Tickets are available from the event website.